Colleen Maynard

Colleen Maynard worked as an artist-in-residence at Prairieside Outpost in November 2017, as part of the first juried residency program. She lives and works in Houston, Texas, and her work is inspired by the biodiversity of the past as she studies fossilized marine invertebrate. The Flint Hills and their location on shale and limestone beds containing sediment of early life served as a treasure trove of investigation for her time at Prairieside Outpost.

Day 2

Class: Uintacrinus

(Subclass: Articulata; Phylum: Echinodermata)

Age: Upper Cretaceous

Distribution: Greenwood, KS; relocated to Johnston Geology Museum, Emporia State University, Kansas

Description: Got in yesterday. Navigated the countryside in a rental with only the paper Google map directions I’d printed out car (I don’t own a car or smartphone and rarely drive). The last time I was alone for 10 days might have been 13 years ago and it feels wildly freeing to be self-dependent and relatively off-grid. I adore the silence, smells, and small thoughtful details in the cabin; it is a warm, cadmium-lit nest inside the somewhat minimalist landscape of the Flint Hills in November.

Today I drive to Emporia State University’s Johnston Geology Museum, to gather images for a new drawing I will work on for the next 9 days.

Comments: I MUST draw the Crinoid slab from Kansas. (“Plate 328 shows a single specimen of Uintacrinus from The Niobrara Chalk Formation of Kansas. Slabs of this chalk have been containing as many as 250 complete specimens of Uintacrinus, with the arms interlocked. These assemblages have been interpreted as once-floating mats of crinoids up to 35’ long.” (706, The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Fossils, Ida Thompson).) While Kansas lacks your traditional Jurassic dinosaur bones, they well make up for in nearly everything else that lived before, and several things that lived after.

The high of spending time with these fossils and minerals makes me celebratory. I traipse into the small town of Emporia, which is sweet and quaint. Sun’s out, leaves are gold, and I feel like I’m 17 again, exploring Kalamazoo while my college friend’s in class.

Day 3

Limestones

Distribution: “Although the Flint Hills were formed by erosion of gently westward-dipping strata in much the same fashion as the Osage Plains, the Permian limestones of the Flint Hills contain numerous bands of chert, or flint. Because chert is much less soluble than the limestone that enclosed it, weathering of the softer rock leaves behind a clayey soil containing much flinty gravel. The gravelly soil blankets the rocky uplands and slows the process of erosion compared with the rate of weathering in adjacent areas where the limestone bedrock does not contain chert. As a result, the crests of the Flint Hills are at a higher elevation than the territory directly to the west or east, and as topographic land forms, the hills themselves are older than those of adjacent areas.” (18-19, Kansas Geology, Ed. Rex Buchanan)

Comments: I’ve begun cementing routines: jolt my face with cold water, get into clothes laid out the night before, and go out to run. The running is necessary—a thing that allows me to plunk my body into a crouch for hours at a time as I draw.

Many of the rocks here are limestone, chalky and calciferous (cretaceous= Latin for “chalky”). Prone to holding water, they contain crater-like divots and holes. Found two pebbles in the driveway with holes bored through them as if beads. As a rule I don’t take what isn’t mine. Yet I pocket these pebbles thinking they’re the volume of mass I’d find lodged in my boot tread.

Back in the city I was beginning to mistake email and social media checking for routine. I itched for a certain order of things in place before locking my studio door. Here, I’m hyperaware of my hourly value. “Binging” on two back-to-back episodes of a Netflix show feels exorbitantly lazy in the cabin in a way it didn’t in the city.

The dense library in the cabin is both wonderful and terrible. I select a book as though selecting one chocolate in a glass case of truffles. I can see folding into this house like a comforted child, and at once I keep asking: what can this place teach me about how much comfort (and from what healthy sources) I need—and how much discomfort/adrenaline?

Back to drawing sand and rocks.

Day 6

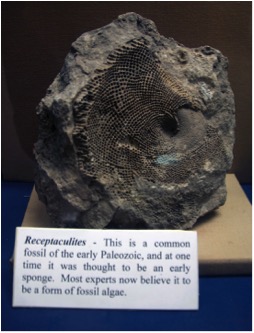

Receptaculitids (Division Chlorophyta)

Age: Precambrian to Recent

Description: “Receptaculitids are the fossils of algae. They lived throughout North America from the Lower Ordivician through the Permian. The surface is covered by rectangular plates arranged in intersecting sets of clockwise and counterclockwise spirals, rather like the arrangement of seeds in a sunflower.” (743, Thompson)

Comments: The creek I pass over on my run has two very different views from either side. On the eastern side, the stream is shallow, with a wide shore of cracking grey limestone and Matfield Shale (“Florence limestone is one of the chert—or flint—bearing limestone that gave Flint Hills their name,” 184, Buchanan). The ledge is gradual and rocky.

The western side of the bridge shows the creek widening, with the mouth angling off into the trees. The field on this side is a bit taller, with the drop-off to the creek a steep 90˚. The erosions in the silt along the bank resemble spread cake frosting. The topsoil of the field runs right up to the edge of the bank, and slightly mushrooms out above the bank as a thin ledge. This ledge, plus the exposed young tree roots cross-sectioned in the bank’s side, reveals that some of this erosion happened recently.

Each time crossing the bridge I try to sit on the steel railing to dangle my legs and catch things I didn’t notice before.

When drawing in the windowed patio room, the morning run still taut in my hips, I think about the wild tomato vines by the road, white horses grazing, and flaky flint boulders.

Day 10

Class: Caninia

(Subclass: Rugosa; Phylum: Cnidaria)

Age: Mississippian

Distribution: Greenwood, KS; relocated to Johnston Geology Museum, Emporia State University, Kansas

Comments: Last day. Ok, while I slept with a steak knife under my pillow here (I see you, isolation), I’ve stumbled on comforts I had not expected. It smacks of clean laundry detergent and mossy forest. I might be 9 years old, running around our friends’ backyard out in the country, or getting lost inside a painting at 13 in my art teacher’s studio. This is the compressed, adult version of growing up weird in a small Midwestern town where I obsessively built paper mache dioramas into the 1 am hour with Dad; where I religiously took my teacher’s stern advise to “be in the studio for an hour before class and another several hours after class like it’s your job.”

As I begin driving back through the Flint Hills, I already can’t wait to start on the hunk of Rugosa Coral embedded in limestone.